When I first read on Google Maps that this neighbourhood is called Pembina Strip, I thought the name was a bit peculiar. The strips that come to my mind are a bit more grandiose: Sunset Strip in Hollywood, the Las Vegas Strip or Macau’s Cotai Strip.

Despite it being listed as “Pembina Strip”, I instinctively called it “the Pembina Strip” or even just “the strip;” I use all three of these variations throughout this post.

The Pembina Strip’s north border is the Best Western on the east side of Pembina Highway and the Golden Door Geriatric Centre on the west side. The Southwest Transitway lines up with the western border of the strip, Abinojii Mikanah at its southern boundary and finally the Red River on the east.

History

Metis River Lots

By 1873, the area of Pembina Strip, far south of the newly incorporated city of Winnipeg (present-day downtown), held a crucial spot in the region with its proximity to the Red River and also the Pembina Trail, an important Métis trading and transportation route (now the Pembina Highway), running through it.

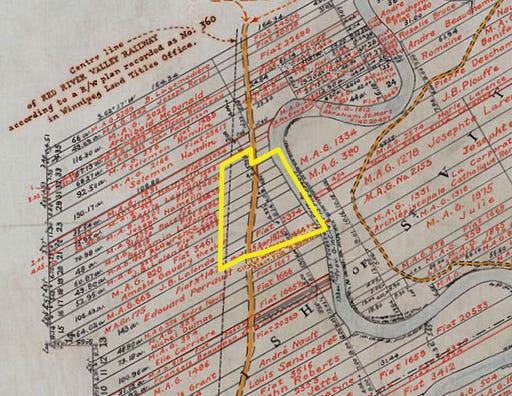

In trying to find what the area looked like during this time, I came across an 1874 map of the larger region south of Winnipeg (Parish of St. Vital and St. Norbert).1

I also came across William Benoit’s comment about the map’s importance and helped to illuminate the larger context.

In post-Confederation Manitoba, the position of the Métis deteriorated. New settlers from Ontario were hostile for racist, religious and cultural reasons. Some Métis elders, over generations, described that period as a “Reign of Terror” against the Métis people. The distribution of land under section 31 [of the Manitoba Act] was slow and fraught with corruption. As a result, many Métis sold their promised interests in the land and moved outside of the province that they had helped to create. The 1874 plan of river lots in the parishes of St. Norbert and St. Vital is included below as an example that depicts the early stages of the Métis diaspora. It also documents land speculation by individuals such as Donald Smith of national railway fame, and the Roman Catholic clergy’s attempt to create and maintain a French-speaking enclave in advance of the oncoming wave of immigration.

Schools and streetcars

In 1880, the strip became part of the Rural Municipality of St. Boniface. A Roman Catholic mission and school operating in the area closed later on in 1887. Twelve years later, the Grey Nuns would open St. Vital No. 1024 school close to the site of the original older school (1750 Pembina Highway).2 After the creation of the City of St. Boniface, the rest of the municipality was renamed St. Vital in 1903, and later in 1912, the lands west of the Red River were reorganized into the Rural Municipality of Fort Garry. Pembina Highway was also paved the same year.3

In 1913, the Agricultural College moved south of the Pembina Strip, in a large bow of the Red River (now present-day University of Manitoba). The expanding streetcar network had streetcar route 97 that ran south alongside Pembina Highway, shuttling people between Winnipeg, Fort Garry, and the college.4

During this time, St. Vital No. 1024's student population grew large enough for a new building to be built in 1912, later becoming a public school in 1917.5

In the 40s, the school was renamed Grandin School and was expanded once again in 1946.6

Pembina Strip, along with a lot of Fort Garry and St. Vital, were completely devastated by the 1950 flood. At least that’s what it looks like according to this map and a variety of different photos I found of the general area.7

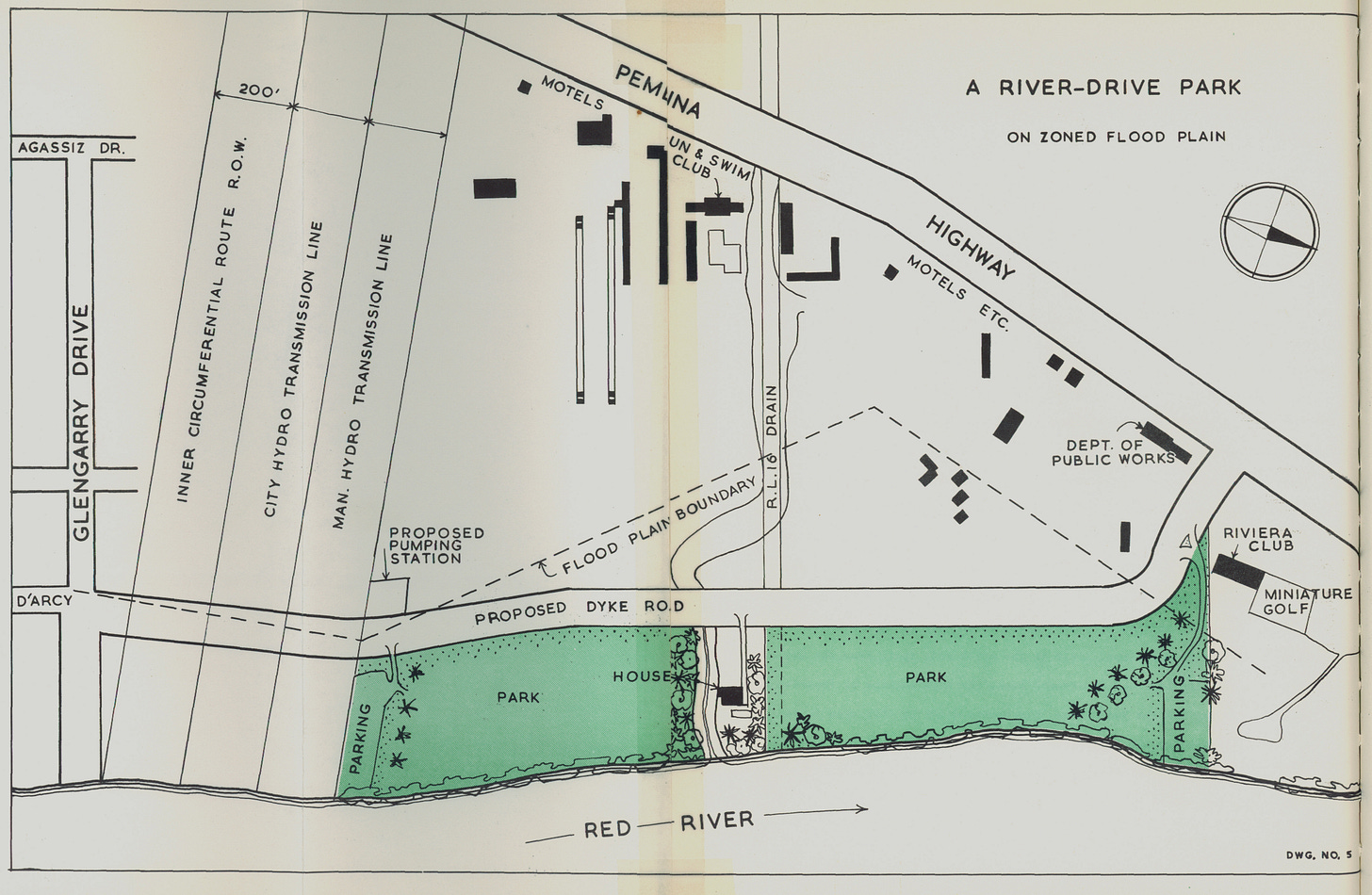

Motels and clubs

By the end of the 1950s, most of the structures on the Pembina Strip were motels, responding to the post-war rise of car culture.8 A look at several insurance plan maps from 1960 showed establishments with names like Aqua Terra Motel, Green Acres Motel, Lazy-U Motel, Nap Ahoy Motel, Eden Roc Motel, and Highwayman Motel.9

The motels wouldn’t just cater to travellers passing through or university students, but also nearby locals, too. According to one Fort Garry resident, if you couldn’t find the Fort Garry police chief Arthur Bridgewater10 at his office, you could find him at the bar at the Le Voyageur Motel, located on the strip.11

Clubs started to spring up in the early ’60s and quickly became hubs for the music and entertainment of the era: local and touring folk singers and, later on, rock bands. The Sun & Swim Club after-dinner’s persona as “The Fireplace” made it “the hottest nightspot in south Winnipeg.”12

In 1963, the Mennonite Brethren built Fort Garry Mennonite Brethren Church at 1771 Pembina Highway, a stone’s throw away from the Sun and Swim Club, close to the Rivera Club and surrounded by other motels. This pairing paralleled the corner of Osborne and Broadway, which at the time had All Saint’s Church on one side and a beer store on the other. On a Winnipeg history Facebook page, one Facebook commentator said, “My dad would say Broadway and Osborne was legislation, salvation, inebriation, and urination.”13 It seemed that the Pembina strip had everything but the legislation.

Post-Unicity14 changes

The ‘70s brought a lot of change to the area, with the Rural Municipality of Fort Garry joining the city of Winnipeg in 1971. Along with amalgamation, the nightclub life on the strip was dealt a blow with the closing of the Sun and Swim club in the mid-70s. A strip mall would replace the club’s spot.15

Residential buildings started to be built, eventually creating the denser look and feel that Pembina Strip has today. Of the current residential buildings on the strip today, the oldest dates back to 1976.

Only a couple of years later in 1978, the building of Bishop Grandin Boulevard (now Abinojii Mikanah) joined the areas of St. Boniface and St. Vital, running over the Red River, merging into Pembina Highway and connecting the area of Fort Garry to neighbourhoods east of the Red River.

In 1986, Mennonite Central Committee Canada’s new head offices at 131 Plaza Drive opened.16 At the time Plaza Drive connected straight onto Bishop Grandin (see map 5).

In 1990, Bishop Grandin Boulevard was built further west to connect with Waverley Street. In 2023, Bishop Grandin Boulevard was renamed Abinojii Mikanah which means “children street” in Ojibwe.17

Photos observations

I started in the northwest corner of the strip, biking south along Pembina and weaving into residential areas and businesses.

Here are several snippets of audio that I captured throughout the neighbourhood walk. Give it a listen while you scroll through the photos

Georgetown Park Apartments surprised me. Two and three-story complexes with public recreational spaces in the middle allow for lively gatherings of families.

As I continued to bike further south on the west side, it turned into mostly strip malls and other commercial businesses.

After reaching the southern edge of Pembina Strip, I crossed over and began to explore the eastern side.

Having seen a lot of businesses and apartment complexes, I decided to bike to Plaza Drive Park at the southeastern edge of the strip. Besides the Southwest Transitway’s green space, the park and the areas along the river are the only other large outdoor public spaces.

Map index:

Map 1: McPhillips, George. Plan of River Lots in the Parishes of St. Norbert and St. Vital, Province of Manitoba / Plan des lots riverains dans les paroisses Saint-Norbert et Saint-Vital (province du Manitoba). April 1874. ITEM 4159931. Library and Archives Canada, e011205909. Accessed December 26, 2024. Accessible at Flickr.

Map 2: Chataway, C. C. Chataway's Map of Greater Winnipeg Enlarged & Revised Edition Including the City of Winnipeg, City of St. Boniface, Town of Tuxedo, Town of Transcona, and Parts of the Municipalities of Assiniboia, Charleswood, Rosser, East Kildonan, West Kildonan, Springfield, Fort Garry, and Saint Vital [map]. Scale not given. Winnipeg: The Western Map Company, 1917. Compiled from official records and surveys by C.C. Chataway, Manitoba Land Surveyor. Image courtesy of University of Manitoba: Archives & Special Collections. Accessed December 20, 2024. Accessible at Flickr.

Map 3: Red River Basin Investigation, Water Resources Division. Greater Winnipeg Flooded Area 1950 [map]. Scale 1:13,650. In: Report on Investigations into Measures for the Reduction of the Flood Hazard in the Greater Winnipeg Area. Ottawa: Department of Resources and Development, Engineering and Water Resources Branch, 1953, plate 5. Accessed December 22, 2024. Accessible at Flickr.

Map 4: Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg. Pembina Highway [map]. Scale not given. In: River Banks in Metropolitan Winnipeg. Winnipeg: Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg, Planning Division, 1964, drawing 5. Accessed December 21, 2024. Accessible at Flickr.

Map 5: Province of Manitoba, Surveys and Mapping Branch. AK36 Riverview [map]. 1:20,000, UTM Zone 14, NAD 1983. Winnipeg: Province of Manitoba, 1990. Contour interval 5 metres. Source: University of Manitoba Libraries Map Collection. Accessible at Flickr.

My attempt of reading the names of those whose river lots are in the area of Pembina Strip is as follows: Basil Laurence, Joseph Hamelin, Marie Racette, Benjamin Lafond, P. Lawrence, J.B. Lalonde, Amable Gaudry the elder. I’m not guaranteed that my deciphering of the names was entirely correct. The linked names lead to information that might match their name and life details.)

Manitoba Historical Society. "Grandin School." Historic Sites of Manitoba. Manitoba Historical Society. Accessed December 30, 2024. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/grandinschool.shtml

Fort Garry Historical Society Inc. Fort Garry Remembered: Stories Collected in and About the RM of Fort Garry, Manitoba. Winnipeg: Fort Garry Historical Society Inc., Show Printing, 2000, 4

Wyatt, David A. Winnipeg Electric Company Trams. Accessed Dec 16, 2024. https://home.cc.umanitoba.ca/~wyatt/alltime/pics/winnipeg-weco-trams.html.

Manitoba Historical Society, "Grandin School."

Ibid.

I found the photos here: https://news.umanitoba.ca/flood-memories-of-winnipeg/. Most of them are of the University of Manitobaa, and if you squint and look at the areas in the distance, you can make out certain areas of Pembina Strip.

There was still the old St. Vital No. 1 school building, but it had closed in 1952 and was used by the Public Works Department and Nuclear Enterprises Ltd until 1971 when the building was demolished.

You can find all of the maps in this Flickr album here. The maps that cover Pembina Strip are 13 through 17.

The residential development of Bridgewater was named after him.

Fort Garry Historical Society Inc. Fort Garry Remembered: Stories Collected in and About the RM of Fort Garry, Manitoba. Winnipeg: Fort Garry Historical Society Inc., Show Printing, 2000, 68

Einarson, John. "The Endless Party." Winnipeg Free Press, December 8, 2013. Accessed December 26, 2024. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/breakingnews/2013/12/08/the-endless-party.

This act of unification of all the surrounding municipalities in the Greater Winnipeg area into one city in 1971 became known as “Unicity”. The word is now used as shorthand for the amalgamation.

Fort Garry Historical Society Inc. Fort Garry Remembered: Stories Collected in and About the RM of Fort Garry, Manitoba. Winnipeg: Fort Garry Historical Society Inc., Show Printing, 2000, 68

MCC Canada and MCC Manitoba would be located there until the two organizations both moved out to different locations downton and the building was sold in 2023.

Manitoba Historical Society. "Bishop Grandin Boulevard." Accessed December 26, 2024. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/bishopgrandinboulevard.shtml.

A seemingly random area when passing through. Always associated with the simple box stores and concrete roads. Goes to show everything has a history. Fun post! Looking forward to the next!

Thank you for including the link to that old river lot map. I now know who held the original grant on my parents' and my grandfather's properties.